Players have shown enormous bravery by sharing their suffering with the world. Now there are clear calls to improve the UK law and ensure kids in sport are better protected

THE BRAVERY OF ANDY WOODWARD

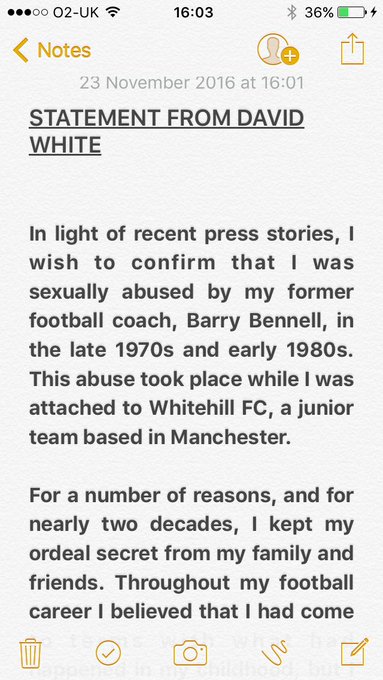

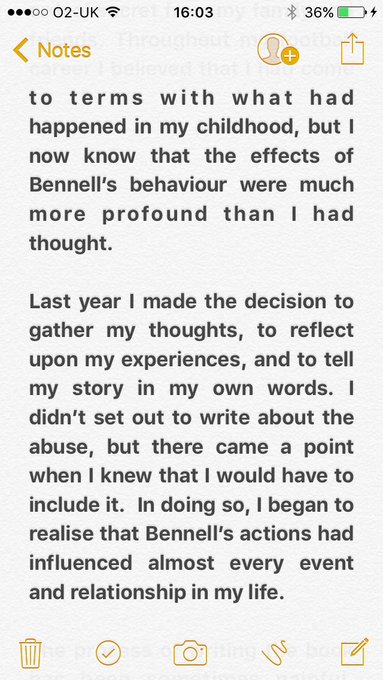

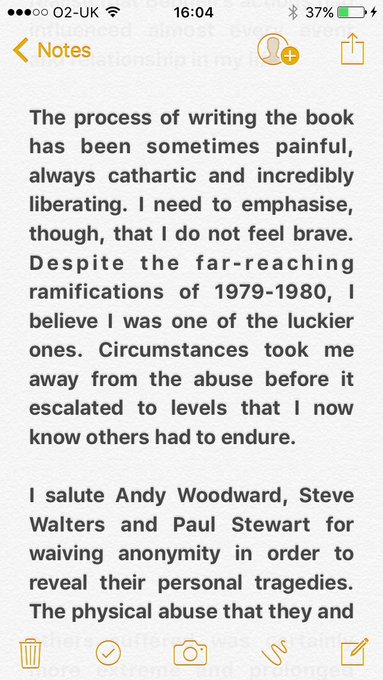

Andy Woodward's career as a professional football player ended when he was 29 years old after spells at Crewe Alexandra, Bury, Sheffield United, Scunthorpe, Halifax and Northwich Victoria. He's not a name that would have been familiar to many football fans before November 16, the day he revealed his horrific sexual abuse at the hands of coach Barry Bennell.

The word 'brave' is bandied about carelessly in sports media ('what brave defending'; 'that was a brave tactical decision'), but when Woodward gave up his anonymity to publicly tell his harrowing story, it constituted real bravery.

Andrea Belotti is the new Vieri

Woodward's promising career was ruined by a paedophile who abused him from the age of 11 during his time at Crewe. His life was destroyed by Bennell, a man whom he had watched – in mortified silence – marry his sister. He has contemplated suicide several times as an adult because of torturous abuse he experienced decades ago as a child within the supposedly safe confines of a football club.

Mike Hartill, author of 'Sexual Abuse in Youth Sport' and senior lecturer at Edge Hill University, explains why football at a junior level is so appealing to those who want to groom children – and why they get away with it.

“Football, simply by virtue of the number of people that participate in it, will have more cases of abuse than other sports,” he told Goal. “There is lots of child abuse that has occurred and been hidden and concealed.

“One thing we do know from sports cases is the power of the coach. The power of the individuals involved, it often means that they operate like families. We can all imagine how hard it would be to report a case of abuse on a family member.”

A couragoeus & hugely significant disclosure by @AndyWoodward2 bit.ly/2eFeqps See bit.ly/1TOWw0Y & voicesfortruthanddignity.eu/information/

Woodward's bravery has opened a can of worms many in football would have secretly hoped would stay shut. The FA, to its credit, is one of the only sport governing bodies to commit significant financial resources to research their own practices and their own sport.

However, the FA is an institution and, like schools and religious organisations, it's driven by a desire to silence bad news. Ian Ackley is one of the victims who gave evidence to put Bennell behind bars in 1998 and he pulls no punches about the fact the FA has a lot to answer for in failing to protect children like him.

"I think the FA surely have an obligation to ensure that organisations under their control are making sure that children are being protected and that their welfare is paramount," Ackley, who was abused countless times over a four-year period by Bennell, told ITV. “They failed to do that and for me are equally as responsible as Bennell because they allowed him to prey on weak and vulnerable young people for years."

Eto'o faces over 10 years in jail

Woodward may have been the first to go public but he certainly won't be the last. More victims are already coming forward. On Tuesday, Steve Walters, a teenage wonderkid in the 1980s, described how Bennell also sexually abused him as a 13-year-old at Crewe Alexandra.

The following day, the Daily Mirror revealed the harrowing abuse suffered by ex-England international Paul Stewart. Stewart's abuse happened at the hands of a different man whom the newspaper didn't name. It's alleged by Stewart, now 52, that the youth coach had threatened to kill his family if he ever told anyone about the sexual crimes committed against him.

HOW FOOTBALL FAILS KIDS

The risk of abuse is so prominent in the sport simply because so many children participate. In July, a survey conducted by the UK government found that 32 per cent of children in the country aged 5-to-10 have played football in the last four weeks, rising to 54% of all 11-to-15-year-olds in the same time span.

“The NSPCC conducted a study a few years ago,” Hartill reveals, “on negative experiences in sport found in a study of over 6,000 university undergraduates that 29% had experienced sexual harassment in sport, 75% emotional harm, 24% physical harm and 3% sexual harm. That says to me that abuse in sport is a very serious and significant problem.”

And that's assuming 3% is truly representative. Realistically, the fact that only university undergraduates aged 18-21 took part in the NSPCC study means all those children lost along the way – whose abuse made them ditch their favoured sport or exit education – are invisible from the statistics. If those victims were taken into account, the percentage would inevitably be higher.

Hartill's Edge Hill University run a campaign called 'Sports Respect Your Rights' that promotes awareness of exploitation, abuse and violence across all sports. It estimates that for every five children in Europe, one has suffered some form of sexual violence.

“The NSPCC, its Child Protection Support Unit [and] Sport England have put world-leading mechanisms in place,” Hartill said, “but we still know far too little on the impact that's having on child welfare."

Defoe is Sunderland's shining light

Bennell's sentencing to nine years in jail in 1998 jolted the FA into creating a 'Charter for Quality' and pledging to rid the game of child abuse. While the actions of the FA were undoubtedly well-intentioned, absolutely nothing changed under UK law. The same systems that allowed him to molest children stayed in place – and remain in place 18 years later.

Tom Perry is the founder of Mandate Now, a pressure group seeking the introduction of mandatory reporting into UK law for people who work in regulated activities – places where the nature of the job means you work closely with children, such as a football coach.

This means that if you were a football coach and you noticed someone else at the club acting suspiciously towards the youth team, you would be under a statutory legal obligation to report it. Seventy-two per cent of Asia, 77% of Africa, 86% of Europe and 90% of the Americas operate some form of mandatory reporting. England, Wales and Scotland don't.

The current way that child protection works in the UK is that reporting on suspected abuse is discretionary – you don't have to do it. You should do, but you won't be held criminally accountable if you don't. Perry believes this allows for powerful forces of persuasion and denial to block the ability to report abuse.

“Let's just say I'm one of the most junior people involved in the academy and I notice something for the third time that raises my suspicions that something untoward could be happening,” he says in a candid interview with Goal.

“If you're reporting it, you feel you have to collect all the evidence – that's impossible, but that's what people expect. And if you report and you are mistaken, you will be crucified.

“So, I turn up and I say 'I saw George go around the corner with this child, it's the third time I've seen it […] and someone looks at you and says, 'oh get lost you muppet, don't be a fool! George wouldn't do that'. And there you go.

“There are hundreds of routes up to the top – even up to the FA – where it can be buried. Were the child protection framework designed to fail, they couldn't have done a better job of it.”

This anecdote is grounded in grim reality. Crewe Alexandra are now facing mounting pressure to explain how Bennell was able to abuse so many children on their watch.

Crewe's current director of football Dario Gradi denies any knowledge of Bennell's activities, despite allegations that at least one incident happened at his home. His comments in June 1998, three days after Bennell was convicted, perfectly illustrate why child protection malfunctions in football.

“Everyone at the club found it hard to believe he was guilty when he was first arrested,” Gradi, who was Crewe's manager between 1983 and 2007, said. “When we first found out what had happened, we were very supportive. All this is now a long time ago and we were untouched by the court case this week. We are all just carrying on as normal.”

On Thursday, Gradi “expressed sympathy to the victims of Bennell” and the club said it had opened an internal investigation. For the victims who have been haunted for decades by the abuse that happened on their watch, it's far too little, far too late.

“I feel massively let down by Crewe,” Walters, the second footballer to reveal his abuses to the public, said last week. “There were always rumours going round about Crewe. The club need to get their heads out of the sand. It was the worst-kept secret in football that Barry had boys staying at his house but nobody at Crewe, as far as I can tell, used to think anything of it. Their reaction is scandalous, really.”

Scholes backs Griezmann for Man Utd

Perry's campaign for better child protection laws stems from the fact he's also a victim of abuse in a sporting environment. As a pupil at Caldicott School in South Buckinghamshire, he suffered abuse at the hands of a rugby coach. It was a scandal that came to light in 2008 in the documentary Chosen.

“Sport is just like schools – they're Petri dishes for abuse,” Perry adds. “You've got the holy trinity for perpetrators. They're close to the people they target, they've got power, secrecy and opportunity, and furthermore there is no requirement to report abuse. You have a perfect environment for abusers.”

Failing to clamp down on child abuse within an institution can have enormously harmful consequences if another abuser gets wind of such activities going unpunished, as Perry describes.

“The power the perpetrator has over a club or a setting is huge. It's deeply worrying. What I've learnt is within sport there's an overwhelming desire to make sure bad news doesn't reach daylight. Conflicted and misguided administrators try to keep the daylight away from concerns and offences, when you actually want the daylight in.”

However, all Crewe are doing is proving how broken the child protection system is in football.

CHILD ABUSE DOESN'T END IN CHILDHOOD

The NSPCC is the 10th-best funded charity in the UK in terms of fundraising income. In 2014/15, the child protection charity raised £109.9 million from donations. However, the difference in funding towards child abuse survivors who make it to adulthood is stark.

The National Association for People Abused in Childhood (NAPAC) is the leading UK charity for supporting that enormous but invisible group of people. It received just £90,000 in donations – that's less than 1% of the figure the NSPCC receives – for 2014/15, its annual turnover was just under £420,000 and it operates with only 10 staff.

“The support for adult survivors has been neglected for a long, long time,” Kath Stipala, NAPAC's head of public affairs, tells Goal. “The issue of what happens to people who were abused in childhood, and the impacts on them into adulthood, have been neglected and still are. It's a major public health issue.

“There's sort of an understanding that children get abused. But what happens for people's adult lives… they may have relationship problems, mental health problems, it might affect their ability to work, their trust may have been destroyed, the impact is really severe on many people.”

That's certainly true of the footballers who shared their stories this month with the UK public. Walters, Crewe's youngest debutant in 1988, arrived at the club a completely different person to when he left after months of abuse from Bennell.

“Before I went to Crewe, I was full of life, full of energy,” he said. “But it knocked the stuffing out of me. I was a confident, outgoing person but sometimes now I can just go into a shell. I have nightmares sometimes and sleeping problems. My wife tells me how I’ve woken up and, straight away, sat bolt upright. I don’t even know I’m doing it. I can have little periods where I am fine but then something might trigger it off.”

Messi is the total footballer

The aftermath of years of abuse for Woodward were just as awful, sometimes hitting him during the middle of games. He said: “The match reports will say I pulled my hamstring but that was just the excuse I used. I’d actually had another full-blown panic attack. We were midway through the first half. I went down to my knees and I just knew I had to get off the pitch. I went to the dressing room and started crying my eyes out, thinking my whole life was ending.”

Woodward and Walters are estimated to be among at least 5 million survivors of child abuse scattered across the UK. An NSPCC report in July 2014 estimated the annual cost of child sexual abuse to the country as £3.2 billion. That's taking into account the impact on the NHS, the justice system, social services and the impact of productivity.

It's a colossal figure and, in the eyes of abuse victim charities such as NAPAC, the best chance of tackling it is by increasing the child safety measures in environments like football academies.

The Prime Minister, Theresa May, has previously dismissed the introduction of mandatory reporting into UK law, but, Stipala points out, she's not basing this on the latest evidence which shows it works.

“She's correct in that if you bring in mandatory reporting, there will be an increase in reports,” Stipala adds, "and if you haven't got the infrastructure to deal with that, it's going to be a problem. But it isn't actually going to be a problem that there will be a lot of false or trivial reports, it'll just be that there will be a lot more substantiated reports of abuse. Teachers aren't suddenly going to start making fictitious reports.”

If Walters is right that it was an open secret at Crewe that Bennell had boys staying at his house all the time, with mandatory reporting there would have been a greater chance of the abuse being raised to authorities.

Hartill says: “We know from previous cases that abuses have often come to light and not officially been reported. I think we need mandatory reporting, the history of child abuse in our country and the extent to which children have clearly been led down by organisations means that we need something considerably stronger.”

The story of Ronaldo's childhood

Yet despite the positive impact experts believe it could have on preventing child abuse from occurring in sports like football, the UK government stubbornly refuses to see it as financially viable. Mandate Now's Perry has torn into what he perceives to be a painfully short-sighted approach.

“Whether it's a school or a football club, the great and good who run these organisations don't want anything happening on their watch,” Perry says, “and when you've got suspected abuse – and you're allowed to ignore it because there is no law to report – then I'm afraid you're in for eternal trouble.

“The government believes that it's going to be an issue of cost and resource but it fails to look at the savings stemming from reductions in crime by abuse victims, drug addiction, prison benefits, and the huge cost to mental health. Until such time as there is mandatory reporting, no reliance can be placed on child protection in any of these settings. That's the problem.”

Woodward's child abuse revelations are already having life-changing impacts – and not just in the glare of the UK media, but behind closed doors too. “Since Andy's first interview it has been nearly all male callers to our support line, normally it is one in four,” Stipala says. “The number of men visiting our website has gone up by 60% in the past few days.”

At least six people are believed to have approached Cheshire Police to report child sex abuse at Crewe Alexandra since Woodward waived his right to anonymity. “I’m convinced there is an awful lot more to come out,” he said. “We were victims in a profession where we were all so desperate to succeed as footballers. We all suffered the same pain.”

Perry believes “everything's different” now that footballers are speaking out in public about their abuses for the first time. He believes that unless the law is changed, many more kids who aspire to be the next Marcus Rashford or having a career like Steven Gerrard's will lose their way at the hands of predators who manipulate the system.

GOAL 50: 50-1

“The government has got to be made to address it, it'll make everybody safer, and it'll make those who are working with children a lot safer as well,” he adds. “Because if they feel they have something to report, the law that exists will protect them. They don't have that at the moment.

“You're placing your child into a place of training [...] where nobody has that power. That's why Jimmy Savile got away from it all that time. It was power, that's why he got away from it and it's an appalling situation.

“It's a huge problem and sadly it's been out of sight. But thanks to people like Andy Woodward and the efforts of lots of other people as well from all different walks of life, gradually this is starting to bubble to the surface. This is the start of something that will carry on rolling now.”

If you want to report non-recent child sexual abuse crimes, please call the police on 101.

If you're an adult survivor of sexual abuse in childhood in the UK, you can call NAPAC’s free confidential support line on 0808 801 0331.

If you're a child who is suffering from sexual abuse, you can call NSPCC's helpline on 0808 800 5000.

Don't suffer in silence, you're not alone. If you need someone to talk to, you can contact The Samaritans on 116 123.

*An earlier version of the article had an image of children playing football with Ibrox in the background. The image has been removed. Goal apologises for any offence this caused, no implication between the club and the scandal was intended to be implied.

No comments:

Post a Comment